#3a──第一印象──FIRST IMPRESSIONS

《智者的啟示》不僅有別於最重要的早期基督教著作,它的敘述複雜性幾乎可以與任何早期基督教著作相匹配。 因此,關於《智者的啟示》的第一件事就是,無論是誰撰寫了《智者的啟示》,他必定花費了大量的時間和精力來構思豐富而複雜的故事情節。 作為研究早期基督教著作的學者,我立即注意到了其他一些令人驚訝的特徵。它所描述智者的家鄉在遠東 Shir 地區這個位置非常不尋常,因為大多數早期的基督徒認為這些智者來自波斯,巴比倫或阿拉伯(請參閱第 14 頁的《智者的崇拜》)。

同樣令人驚訝的是,它與基督本人一起鑒定了伯利恆之星,這種解釋在早期基督徒對這種神秘天體的各種猜測中無處可尋。 使徒多馬遲遲未進入故事中這是出乎意料的,並給我提出了一系列新的問題,涉及《智者的啟示》和其他討論使徒多馬的著作之間的關係。 同時,我也被食物相關的奇怪事件所吸引,因為食物與其他宗教傳統中使用的致幻物質具有相似性,從而引起了基督對智者和希爾 (Shir) 人民的異象。

但最後也是最重要的是,也是令我驚訝的是,我和我的任何同事都沒有意識到這一令人印象深刻的文本的存在,然後才偶然看到有一篇文章中提及它。 當然,有很多早期的基督教次經著作只為專門從事次經文學的學者所熟悉,但是我和我所諮詢的該領域的其他專家對《智者的啟示》是完全陌生的。 對於我作為一名博士生而言,如此鮮為人知的文本代表了將重要文獻納入早期基督教學術主流的絕好機會。 然而,這對我作為研究人員的技能也是一個嚴峻的挑戰,因為即使是有關何時何情況下寫的這本著作這些基本問題都無法解決。

「 智者的啟示」從何而來?

正如我之前提到的,《東方博士的啟示》以前從未被翻譯成英文,早期基督教次經文學中的專家甚至很少知道它的存在。 這個非凡的著作是怎麼被如此忽略的? 問題的部分原因是該文本的唯一已知副本保存在敘利亞語中,敘利亞語是整個中東和亞洲的古代基督徒使用的一種語言,但是只有一小部分流利的早期基督教學者使用該語言。相比之下,更多的學者知道科普特語,這是一種埃及語言,其中多馬福音,馬利亞福音和猶大福音等重要文本被保存下來。

此文本被忽略的另一個重要原因是,它屬於歷史上在早期基督教研究中被蔑視的兩類材料。 首先,這是一部次經著作,學者們長期以來一直將新約的正典著作享有特權,並排除正典之外的著作。 當然,也有一些例外,例如剛才提到的著作,但是除了這些例外,大多數次經著作仍然受到嚴重的忽視。

其次,《智者的啟示》是少數經典和次經文本之一,其重點是圍繞耶穌誕生的事件。 儘管整個世紀以來,聖誕節的故事都使信徒著迷,但在四本經典福音書中,只有兩個關於耶穌誕生的記載,這表明耶穌的誕生對於第一批基督徒來說,其重要性不如死亡,復活和耶穌的教導重要。 此外,馬太 (Matthew) 和路加 (Luke) 講述了關於耶穌出生的明顯不同的故事,而且這種區別很難輕易協調。 結果,今天的大多數學者認為,這種材料很少聲稱具有歷史性。大家主要關注耶穌的言論和他在耶路撒冷的最後日子。 僅有少數新近學者在耶穌嬰兒期故事中發現一些可靠的歷史細節,而《智者》的故事也不是其中之一。

即使今天鮮為人知,包含《智者的啟示》的手稿也從未真正丟失過──肯定不會像《死海古卷》那樣丟失。 在八世紀末,一位匿名的修道士將現有手抄本在土耳其東南部的 Zuqnin 修道院抄下來後,在某個時候將其易手,並保存在埃及沙漠的一家修道院中。 在那裡一直呆到 18 世紀,當時阿塞瑪尼 (G.S. Assemani) 代表梵蒂岡圖書館收藏了手稿,並將其帶到了今天的羅馬。.

儘管這本手稿已經被歐洲學者研究了數百年,但直到最近學者們才開始仔細研究它所包含的《智者》的傳說。1950 年代有人譯出了《東方博士的啟示》的義大利語譯本。幾十年來,人們經常在週邊文章中討論該文本。 偶然地,當我首先知道了《智者的啟示》的存在,那時我剛完成第一年的學習敘利亞語言。 因此,我已經做好充分的準備,可以在哈佛大學敘利亞語科克利教授的幫助下開始翻譯英文譯本。 在與科克利教授進行為期兩年的雙周會議以檢查我的工作後,我設法完成《智者的啟示》的粗略而完整的翻譯。 儘管有很多必需的工作,但我作為早期基督教著作學者的任務才剛剛開始。 不像其他從事新約經文甚至著名的次經著作的研究的學者,沒有關於我要開始翻譯的《智者的啟示》的既有「對話」資料。很少學者們知道這個文本的存在,所以關於它有多古老,只有一些初步的關於智者的啟示可能是誰寫的,以及它的創作地的資訊資料。

為了弄清楚最可能的創作日期,我的第一步是從最晚的時間開始確認該文本可能已經寫好的時間,然後盡可能地向後推測。 如前所述,僅有的《智者的啟示》的一個副本,而且該手稿已可靠地註明日期於八世紀末。 撰寫此手稿的匿名抄寫員是否可能實際上就是《智者的啟示》的作者? 不太可能,原因有幾個。 首先,一般來說,學者很少知道早期的基督教徒手稿的日期,那些手稿很少註明成稿的日期。其次,手稿本身──被稱為 Zuqnin 紀事,是修道院的編年史──包含許多已知成書於八世紀之前的著作。第三,一位生活在阿拉伯半島的基督徒作家希歐多爾.巴.科奈幾乎在撰寫該編年史的同時,也對《智者的啟示》有所瞭解。 沒有理由懷疑《Zuqinn 紀事》是從土耳其東南地區傳到阿拉伯沙漠的時間僅短短幾年。 《智者的啟示》似乎更有可能是智者的著作早於八世紀就被寫成並廣為流傳。

但是要早多久呢?幸運的是,即使我們只擁有《智者的啟示》的完整副本,關於智者的這段經文還有另一個非常重要的見證。 另一位證人是馬太福音,通常被認為寫於五世紀,並為學者所熟知作為《不完美的歌劇》(Opus Imperfectum) 之評論的匿名作者 Matthaeum,當他看到馬太福音中關於《博士》的故事講述了有關這些神秘人物的傳說。 即使他僅用幾小段就總結了這個傳說,顯然和智者的啟示相吻合。此外,他很有可能實際上已經看過智者的啟示這本書的書面副本,因為他的摘要中有幾個部分實際上是與現存的《智者啟示錄》副本逐字一致的。

因此,可以肯定的是《不完美的歌劇》(Opus Imperfectum) 是寫於五世紀。 但是我們怎麼知道《智者的啟示》的敘利亞文本寫的時間早於西元五世紀?畢竟,這個傳說以一種形式已大大傳播。敘利亞文字中有一個很小的看似微不足道的細節,這個細節告訴了我們這本書是什麼時候寫的。 在敘利亞語中,名詞可以是男性或女性,而在在智者的啟示中,「聖靈」是一個女性名詞。 雖然今天可能會讓我們感到驚訝,認為聖靈是一個女性實體,這經常出現在第二、第三世紀很多位原敘利亞作家的作品中,直到第四世紀。然而,從五世紀開始,敘利亞作家開始在希臘基督教思想的影響下,將「聖靈」作為男性名詞。 這是什麼意思?意思就是說敘利亞語言本身證實了《智者啟示錄》的書寫形式必早於五世紀寫成。

敘利亞語的這個傳統告訴我們,這個文本必是早於第五世紀寫的。為了確定它成書早了多少年,我們需要在敘利亞語《智者的啟示》中尋找其他線索。在《智者的啟示》的總結中回想一下。在早些時候提出的《智者的啟示》的摘要中回想一下。我認為使徒多馬與智者的交集的故事最初可能不是《智者的啟示》的一部分。不只是從敘事的角度來看,它似乎多餘,從文學功能來看也不適合。首先,多馬情節敘述用的是第三人稱,而《智者的啟示》的其餘部分是由智者自己敘述,用的是第一人稱。雖然這種轉變在敘述者的角度也不是聞所未聞,但在古代基督教著作中,這種轉變是特別突然和無法解釋的現象。第二,多馬的情節與第一人稱術語相比還包含另一個驚人的不同之處,《智者的啟示》最顯著的特點之一是用第一人稱敘述的部分完全避免正確的名稱和稱呼「耶穌基督 」指神之存在,正如作者小心翼翼地放棄這個名字和其他明顯的基督教術語,多馬部分的敘述完全不去避免「耶穌基督」的名稱,使用它近 20 次 !

由於這些原因,我相信多馬的情節是後來放進《智者的啟示》裡的。我會說也有可能還有更多的原因,比如有人可能想篡改文本,聲稱《智者的啟示》是關於基督的到來的真實見證。但現在讓我們使用多馬的情節,以找出更多關於《智者的啟示》是何時寫成的證據。或者至少當它被篡改的時候,碰巧有關於使徒多馬的故事在生活在敘利亞的古代基督徒中特別受歡迎。這些故事中最著名的收集品被稱為使徒多馬的啟示,它包括他所行的神跡、他的教導和事蹟。他最終在印度殉道。即使多馬的行為和情節在《智者的啟示》中講的是不同的故事,他們用他們的語言和神學分享許多情節。這些相似之處表明,多馬的情節可能是後添加進去的。與《智者的啟示》大約同一時間,其他有關多馬的傳說正在寫下來──也就是說,大約在第三世紀末或四世紀初寫於敘利亞。因此,第一人稱形式的《智者的啟示》一定也是在這個時間寫成的。最晚,也許更早,如果它來自敘利亞以外的地方。

但是《智者的啟示》的最初形式能寫得早多少呢?可能正如它所聲稱的,這是智者自己的真實證詞?這個說法有著其誘人的可能性。可能是這樣,也極可能不是這樣。首先,整個智者故事是歷史上真實發生的事情,被記錄於馬太福音。如前所述,學者們已經得出結論。在《新約》中所記載的關於耶穌幼年的敘事中,幾乎沒有任何具有歷史價值的東西。這決定了被記錄的智者的故事擁有著特別的活力。故事的特點,即使最令人印象深刻的伯利恆之星,都是從來無可爭議,相反的論點都是站不住腳的。事實上,智者的故事的痕跡被發現在路加所記述的關於耶穌幼年的敘事中,有卑微的牧羊人作為新生兒耶穌的第一個外部證人。任何其他最早的基督教著作都不能提高它的可信度。

但是,即使我們承認在馬太福音中智者是基於一個實際的歷史事件,《智者的啟示》也不會是一個有非常強大吸引力的見證,這個見證是智者寫自己的經歷。誠然,《智者的啟示》的作者精心寫下了這個故事,並增加了很多的細節。一旦我們密切關注這些,任何人都可能會相信這是智者自己的工作。然而,當我們仔細讀這個故事,它變得很明顯,作者已經使用了書面來源──如使徒保羅的信、約翰福音和啟示錄。這些人在寫十年後的「歷史性智者」時幾乎都不在世了。

事實上,作者不僅使用了《新約》中許多最早的基督教著作,他似乎也使用了一個相當晦澀難懂的啟示福音,可能寫在第二個世紀中後期。一個福音書如此晦澀,它缺乏一個通俗名稱!為了表述得更清晰,讓我們稱之為嬰兒福音 X 。在嬰兒福音 X 書中記載智者來拜訪新生兒耶穌,在伯利恆村外一個洞穴。約瑟──在嬰兒福音 X 書中的主要成員,而不是在馬太和路加福音中的敘述的那樣,在這兩本福音書中從來沒有說起過這樣一件事──約瑟 一直都在質疑這些奇怪的遊客是如何知道孩子的出生的。

在隨後的與約瑟的對話中,智者提到了一些細節,這些細節被寫進智者的啟示。這些細節包括通過學習他們自己的非常古老的著作,他們學會了如何辨別恆星,在漫長的旅程中智者疲勞的時候,他們可以單獨見到那顆難以形容的明亮的星星,這顆星賜給他們力量。約瑟甚至猜測智者是占星家,因為他們不斷抬頭看天空,顯然是看著別人所看不見的天體指南。啟示錄中發生了一個非常相似的場景,但那是耶路撒冷的領導人,而不是約瑟。誰都看不到這顆星星,唯有智者可以看到。最後,嬰兒福音 X 記載的東方博士不是三個數位,而是一個更大的群體──這也在《智者的啟示》中的一種暗示 ( 見第 27 頁的《智者的崇拜》)。

這些相似之處是非常驚人的,但在嬰兒福音 X 所有這些細節都緊緊集中在智者在伯利恆洞穴的短暫出現,沒有像智者的啟示那樣蔓延到整個敘述。似乎很有可能,有某種文學關聯。這兩個作品是誰借鑒誰 ?這是很難說的。甚至是可能這兩部作品的作者使用第三個來源(無論是口頭的還是書面的),獨立於彼此。我自己已經來回多次更多研究關於哪個寫作更老。在做出果斷判斷之前,有必要先進行研究嬰兒福音 X 。

即便如此,如果我們假設智者的啟示是在嬰兒福音 X 之後的某個時候而成的,那麼它可能是寫在第二世紀末或三世紀初。然後,它在第三世紀後期,或第四世紀初做了更新,添加關於使徒多馬的訪問結束敘述。

如果智者的啟示不是像它所聲稱的是由智者自己寫的,那麼又有誰可能寫了這個奇怪的故事呢 ?雖然有可能有人以足夠的信心和時間在那個時期把它寫成,但關於作者的特徵或位置的資訊資料微乎其微,只有少量的早期基督教著作中有所提及。不管怎樣, 馬吉的啟示的作者與其他著作的作者沒有太大的不同,這些作者所在的地方同樣不可知 :關於作者的複雜神學──我們將暫時以一個城市位置來解決,也許羅馬,亞歷山大,安提阿,以弗所,或羅馬世界的另一個主要城市中心。正如我們所知,智者的啟示是寫於君士坦丁堡(為在那裡發現其中一個叫奧普斯的作者在第五世紀,在土耳其東南部 一個匿名修道士在祖克寧修道院複製它),到八世紀末流傳於阿拉伯半島(希歐多爾酒吧科奈居住的地方)。

然而,即使我們不知道很多關於作者的身份和行蹤,實際上我們可以從相當多的其他基督教信息中理解為什麼智者的啟示後來被視為神學上的危險。

摘自《智者的啟示》

承蒙神召會活水堂授權【葡萄樹傳媒】轉載

FIRST IMPRESSIONS

──Brent Landau

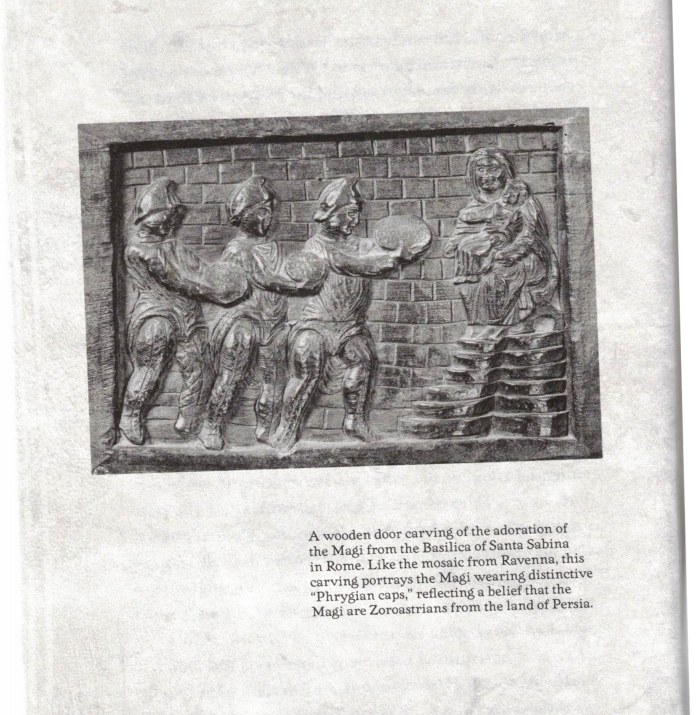

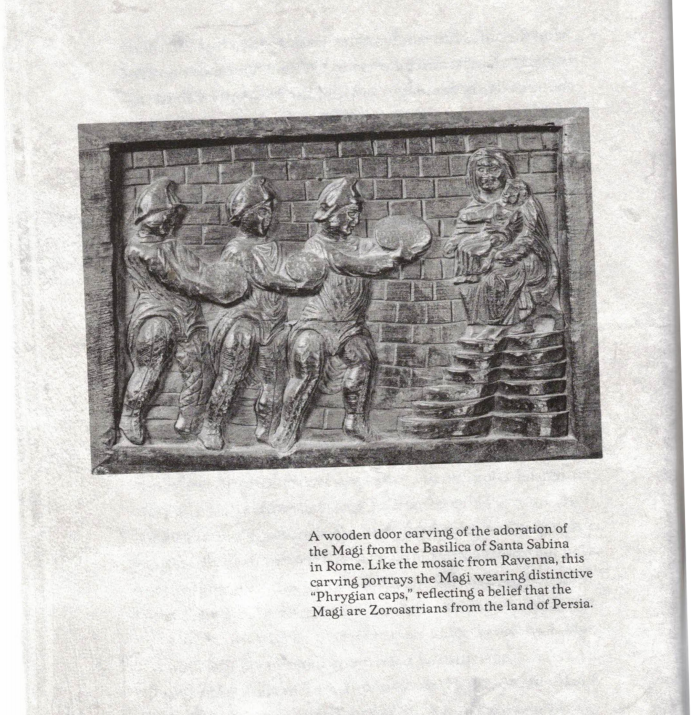

Not only does the Revelation of the Magi have the distinction of being the most substantial early Christian composition about the Magi; its narrative complexity matches almost any early Christian writing. Thus, the first thing that one notices about the Revelation of the Magi is that whoever wrote it devoted a great deal of time and thought to crafting a rich and intricate story line. As a scholar of early Christian writings, I noticed several other surprising features immediately. Its location of the Magi in the far-eastern land of Shir was highly unusual, since most early Christians thought that the Magi came from Persia, Babylon, or Arabia (see Adoration of the Magi on page 14).

Also surprising was its identification of the Star of Bethlehem with Christ himself, an interpretation found nowhere else in the diverse array of early Christian speculation about this mysterious celestial portent. The late entry of the Apostle Thomas into the action of narrative was quite unexpected, and raised a new series of questions for me about the relationship between the Revelation of the Magi and other texts that discuss the Apostle Thomas. I was also captivated by the very strange incident of the food that produced visions of Christ for the Magi and the people of Shir, given its parallels to the use of hallucinogenic substances in other religious traditions.

But finally and most importantly, I was surprised that neither I nor any of my colleagues knew of this impressive text’s existence before I stumbled across a mention of it in an article. There are certainly a significant number of early Christian apocryphal writings that are familiar only to scholars specializing in apocryphal literature, but the Revelation of the Magi was completely unknown to me and to other specialists in this field that I consulted. For me as a doctoral student, such a poorly known text represented a wonderful opportunity to bring an important document into the mainstream of early Christian scholarship. Yet it would also prove to be a serious challenge to my skills as a researcher,since even basic questions about when and under what circumstances it was written were unresolved.

WHERE DID THE“REVELATION OF THE MAGI” COME FROM?

As I mentioned earlier, the Revelation of the Magi has never before been translated into English,and very few specialists in early Christian apocryphal literature even know of its existence. How did this remarkable text come to be so neglected? Part of the problem is that the only known copy of the text is preserved in Syriac, a language used by ancient Christians throughout the Middle East and Asia, but one in which only a relatively small number of early Christian scholars are fluent. By comparison, many more scholars know Coptic, an Egyptian language in which such importance texts as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Mary, and the Gospel of Judas have been preserved.

Another important reason for this text’s neglect, however, is that it belongs to two categories of material that historically have been scorned in the study of early Christianity. First, it is an apocryphal writing, and scholars have long privileged the canonical writings of the New Testament to the exclusion of writings outside of the canon. There are, of course, a few exceptions, such as the writings just mentioned, but beyond these, most apocryphal writings remain sorely neglected. Second,the Revelation of the Magi is one of a handful of canonical and apocryphal texts that focus on events surrounding the birth of Jesus. Although the Christmas story has fascinated believers throughout the centuries, there are only two accounts of Jesus’s birth among the four canonical Gospels, suggesting that the birth of Jesus was not nearly as important for the first Christians as the death, Resurrection,and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. Furthermore, Matthew and Luke tell markedly different stories about Jesus’s birth , and the difference cannot be easily harmonized. As a result, the great majority of scholars today believe that this material has very little claim to historicity Jesus has mostly focused on his sayings and his final days in Jerusalem; only a few recent scholars have found any reliable historical details in the infancy narratives – and the story of the Magi is not one of them.

Even if it is poorly known today, the manuscript that contains the Revelation of the Magi was never truly lost – certainly not in the way that, say, the Dead Sea Scrolls were. After the existing manuscript was copied down at the Zuqnin monastery in southeastern Turkey by an anonymous monk at the end of the eighth century, it changed hands at some point and was kept in a monastery in the Egyptian desert. There it stayed until the eighteenth century, when G.S. Assemani,collecting manuscripts on behalf of the Vatican Library, brought it to Rome, where it resides today.

Through this manuscript had been known by European scholars for several hundred years, it was not until rather recently that scholars first began to look closely at the legend of the Magi that it contained. An Italian translation of the Revelation of the Magi was made in the 1950s, and a few scholars in the decades since have discussed the text in journal articles, often peripherally. Quite serendipitously, when I first learned of the existence of the Revelation of the Magi, I had just finished my first year of studying the Syriac language. I was therefore well prepared to begin translating the text with the help of J. F. Coakley, Professor of Syriac at Harvard.

After nearly a year of biweekly meetings with Professor Coakley to check my work, I had managed to produce a rough but complete translation of the Revelation of the Magi. Despite the many hours of work that this had required, my task as a scholar of early Christian writings was only beginning.Unlike a scholar working on a New Testament text or even a well-known apocryphal writing, there was virtually no preexisting “conversation” about the Revelation of the Magi into which I was entering.Very few scholars knew that the text existed at all, so there were only some tentative suggestions about how old the Revelation of the Magi might be, who might have written it, and where it was composed.

To figure out the most likely date of composition, my first step was to start with the latest possible time the text could have been written and then work backward as far as possible. As mentioned earlier, there is only one copy of the Revelation of the Magi in existence, and that manuscript is securely dated to the late eighth century. Is it possible that the anonymous scribe who wrote this manuscript was actually the author of the Revelation of the Magi? Not likely, for several reasons. First, as a general matter, scholars of early Christianity know that the date of a manuscript is very rarely the date of the text it contains. Second, the manuscript itself – known as the Chronicle of Zuqnin, for the monastery in which it was written – contains a number of writings that are known to have existed much earlier than the eighth century. Third, a Christian writer named Theodore bar Konai, who lived on the Arabian Peninsula at almost the same time that the3 chronicle was written, seems to have known about the Revelation of the magi. There is no reason to suspect that the Chronicle of Zuqnin would have traveled from southeastern Turkey to the Arabian Desert in the span of only a few years. It seems far more likely that the Revelation of the Magi was written – and circulated rather widely – earlier than the eighth century.

But how much earlier? Fortunately, even though we possess only one full copy of the Revelation of the Magi, there is another very important witness to this text. This other witness is a Latin commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, usually thought to have been written in the fifth century and known by scholars as the Opus Imperfectum in Matthaeum. The anonymous writer of this commentary, when he comes to Matthew’s story of the Magi, relates a legend about these mysterious figures. Even though he summarizes this legend in only a few short paragraphs, it is clearly the same story as that found in the Revelation of the Magi. Moreover, it is very likely that he had actually seen a written copy of the Revelation of the Magi, since there are several parts of his summary that agree, practically verbatim,with the copy of the Revelation of the Magi that has survived for us.

So it seems certain that a version of the Revelation of the Magi existed when the Opus Imperfectum was written in the fifth century. But how do we know that the Syriac text of the Revelation of the Magi that we have was written earlier than the fifth century? After all, it could be a later form of the legend that had been expanded significantly. There is one small, seemingly insignificant detail in the Syriac text that tells us when it was written. In the Syriac language, nouns can be either masculine or feminine, and in the Revelation of the Magi, “the Holy Spirit” is a feminine noun. Although it might surprise us today to think of the Holy Spirit as a female entity, this is exactly what Syriac writers of the second, third, and fourth centuries considered it/her. Starting in the fifth century, however, Syriac writers began to treat “the Holy Spirit” as a masculine noun, under influence from Greek Christian thought. What this means, therefore, is that the Syriac language itself confirms that the form of the Revelation of the Magi that we possess must have been written earlier than the fifth century.

But this quirk of the Syriac language tells us only that the text must have been written earlier than the fifth century. To determine how much earlier it was written, we need to look for other clues in the Syriac form of the Revelation of the Magi. Recall that in the summary of the Revelation of the Magi. Recall that in the summary of the Revelation of the Magi presented earlier. I suggested that the story of the Apostle Thomas’s conversion of the Magi was probably not originally part of the Revelation of the Magi. Not only does it seem superfluous from a narrative point of view, but it also has a number of literary features that do not fit very well with what has come before. First, the Thomas episode is narrated in the third person, whereas the rest of the Revelation of the Magi is narrated by the Magi themselves, in the first person. Although such shifts in the perspective of the narrator are not unheard of in ancient Christian writings, this shift is especially abrupt and unexplained within the narrative. Second, the Thomas episode contains a striking change in terminology as compared with the first person section of the Revelation of the Magi. One of the most distinctive features of the first-person section is its complete avoidance of the proper name “Jesus Christ” to refer to the divine being when the Magi encounter. Yet as careful as the author is to forgo this name and other obviously Christian terminology, the Thomas section is not at all concerned to avoid the name “Jesus Christ,” using it almost twenty times!

Because of these reasons, I believe that the Thomas episode was a later addition to the Revelation of the Magi. I will say more shortly about the reasons that someone might have wanted to tamper with a text that purported to the authentic testimony of the Magi about the coming of Christ. But for now,let us use the Thomas episode to help find out more about when the Revelation of the Magi was written – or at least when it was tampered with. As it happens, stories about the Apostle Thomas were especially popular among ancient Christians living in Syria. The most famous collection of these stories is known as the Apocryphal Acts of the Apostle Thomas, and it includes accounts of his miracles, his preaching and his eventual martyrdom in India. Even though the Acts of Thomas and the Thomas episode from the Revelation of the Magi do not tell the same story, they share numerous connections in their language and theology. These similarities suggest that the Thomas episode was probably composed and added to the Revelation of the Magi around the same time and place as other Thomas legends were being written down – that is, around the late third or early fourth century in Syria. Therefore, the first-person form of the Revelation of the Magi must have been composed by this time at the latest, and perhaps earlier if it came from some place outside of Syria.

But how much earlier might the original form of the Revelation of the Magi have been written? Might it be, as it claims, the authentic testimony of the Magi themselves? As tantalizing a possibility as this might be, it is highly unlikely. First of all, there is the basic problem of historicity with the whole Magi story found in Matthew’s Gospel. As mentioned earlier, scholars have by and large concluded that there is virtually nothing of historical value in the infancy narratives of the New Testament. This judgement has been applied with particular vigor to the Magi story. Even the Star of Bethlehem,the most impressive feature of the story, has never been incontrovertibly identified, arguments to the contrary not with-standing. And the fact that no trace of the Magi story is found in Luke’s infancy narrative, which has the humble shepherds as the first outside witnesses to the child Jesus, or in any other of the earliest Christian writings does not enhance its credibility.

But even if we were to grant that Matthew’s story of the Magi was based on an actual historical event, the Revelation of the Magi would not be a very strong candidate to have been written by the Magi themselves. True, the author of the Revelation of the Magi has carefully crafted this story and added levels of detail such that one might believe it to be the work of the Magi themselves. Once we closely inspect the story, however, it becomes clear that the author has used written sources – such as the letters of the Apostle Paul, the Gospel of John, and the Book of Revelation, to name a few – that were written ten years after the “historical Magi” almost certainly would have died.

In fact, the author not only used many of the earliest Christian writings in the New Testament. He seems to have used a rather obscure apocryphal Infancy Gospel that was likely written in the mid to late-second century, a Gospel so obscure that it lacks an agreed-upon name! For the sake of (some) clarity, let us call it Infancy Gospel X. In infancy Gospel X, the Magi come to visit the child Jesus at a small house outside the village of Bethlehem. Joseph – the main actor in Infancy Gospel X, as opposed to the narratives in Matthew and Luke, where he never says a work – proceeds to question these strange visitors about how they knew of the child’s birth.

During the ensuing dialogue with Joseph, the Magi mention a number of details corroborated by the Revelation of the Magi. These include learning of the star’s coming through their own very ancient writings, the Magi’s lack of fatigue after a lengthy journey, and the indescribably bright star being visible to the Magi alone. Joseph even presumes the Magi to be astrologers because the keep looking up at the sky, apparently watching their invisible celestial guide. A very similar scene takes place in the Revelation of the Magi, but there it is the leaders in Jerusalem, not Joseph, who cannot see the star. Finally, Infancy Gospel X envisions the Magi not as three in number, but as a much larger group – an interpretation hinted at in the Revelation of the Magi (see The Adoration of the Magi on page 27).

These parallels are very striking, but in Infancy Gospel X all these details are tightly concentrated in the Magi’s brief appearance at the Bethlehem cave, not spread throughout the narrative as in the Revelation of the Magi. It seems quite probable that there is some sort of literary relationship between these two works, but who has borrowed from whom? It is very difficult to tell, and it is even possible that the authors of these two works used a third source (whether oral or written) independently of each other. I myself have gone back and forth many times about which writing was older. More research on Infancy Gospel X would be necessary before a decisive judgment could be made.

Even so, if we assume that the Revelation of the Magi came into being sometime after Infancy Gospel X, then it was probably written in the late second or early third century. It was then “corrected” in the late third or early fourth century by adding the concluding narrative about the Apostle Thomas’s visit to the Magi.

If the Revelation of the Magi was not, as it claims, written by the Magi themselves, then who might have written this strange story? Although it is possible to give, with a reasonable degree of confidence,a window of time during which it was composed, we have almost nothing to go on regarding the author’s identity or location. Only a small number of early Christian writings are written in the person put forth as the author anyway, so the Revelation of the Magi is not much different from them in the respect. The place of authorship is similarly unknowable: presumably the author’s sophisticated theology – which we will address momentarily – suggests an urban location, perhaps Rome, Alexandria,Antioch, Ephesus, or another major urban center of the Roman world. All we know is that the Revelation of the Magi was known in Constantinople (where the author of the Opus Imperfectum found it) in the fifth century, and in southeastern Turkey (where an anonymous monk at the Zuqnin monastery copied it) and the Arabian Peninsula (where Theodore bar Konai lived) by the end of the eighth century.

Yet even if we cannot say much of anything substantial about the identity of the author or his whereabouts, we can actually say quite a bit about his understanding of the Christian message, and about why his understanding might have been viewed as theologically dangerous enough to warrant a new ending for Revelation of the Magi.

支 持 我 們

靈修小品:

# TAG

EN English MONDAY MANNA 中國成語 以色列 以色列新聞 你累了嗎 保捷 信仰見證 出埃及記 利未記 創世記 劉國偉 原文解經 國度禾場KHM 天人之聲 天堂 奇妙的創造 妥拉 妥拉人生 家庭 市井心靈 張哈拿牧師 愛情 敬拜 智慧 梁永善牧師 歳首到年終 民數記 清晨妥拉 清晨妥拉2.0 漫畫事件簿 為以色列代禱 琴與爐 申命記 真理 知識 箴言 考門夫人 聖經 荒漠甘泉 見證 週一嗎哪 靈修 靈修文章